- Home

- Anna Daniels

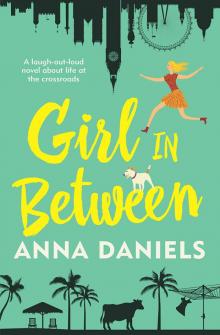

Girl in Between

Girl in Between Read online

First published in 2017

Copyright © Anna Daniels 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Arena Books, an imprint of

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76029 530 1

eISBN 978 1 92557 655 9

Cover design: Romina Panetta

Cover illustrations: iStock/Shutterstock

Internal design by Romina Panetta

For Mum and Dad. And for my friend Ange—we all love and miss you.

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Far out, there’s nothing like a trip to the family accountant to sober you up. I’ve just spent the last forty minutes calling out figures on faded receipts to Todd Doherty, who promised to get my tax return done asap so I don’t have to exist on two-thirds of bugger-all. What’s particularly mortifying is that Todd and I went to high school together, and while he’s probably on a six-figure salary he’s well aware that I’m flat out finding six bucks.

‘Dire’ is the word Todd used to describe my financial situation, although he did say it with a kindly smile, which I appreciated. If only I had assets that were appreciating. My trusty old Corolla, which I’m currently driving to my parents’ house in Rockhampton, is my sole valuable possession—well, that and my Anne of Green Gables collection, and my kelpie, Glenda.

I weave along these wide streets like a dodgem car driver with the rink to myself, knowing when I recount my morning to my bestie, Rosie, I’ll get a great giggle from her.

Ah, Rocky. Our claims to fame are our wide streets, the fact that trains run down the centre of these wide streets, and that the roundabouts within these wide streets are dotted with statues of fibreglass bulls, as befits the Beef Capital of Australia.

Speaking of trains, there’s one whizzing beside me now. I think Rocky is the only place on earth where trains just seem to sneak up and share the road with you. It’s as if one moment they’re all docked at the depot having a cappuccino, and the next they’re tailgating you to Wah Hah Chinese.

I feel a sudden wave of nostalgia as I pass Paradise Plaza and get closer to home because nearly every corner holds a familiar story.

There’s the Hungry Jack’s that used to be a Cash Converters; the laneway beside the cinema where, as teenagers, we’d down West Coast Coolers; and Holy Mackerel the fish and chip shop where we bought dinner on Friday nights. Apparently the new owners of Holy Mackerel recently got done for selling drugs over the counter. Can you imagine? ‘I’ll have two pieces of battered snapper and five dollars’ worth of chips.’ Wink, wink.

Still, you’d be hard pressed to find more salt-of-the-earth, give-you-the-shirt-off-their-back, nylon-football-shorts-wearing people than those of Rockhampton. Mum and Dad are a classic case in point, though Dad doesn’t wear football shorts, thank God. Forty years ago, the two of them started a combined newsagency and after-five dress shop called All About Town. Surprisingly, the combo worked, and eighteen months ago they sold up to a couple from Newcastle who’d promised to keep the business going but within six weeks had converted it into a waxing parlour called Gone Bush.

As I drive past the old shop building now, a rush of memories comes flooding back. Lenny, Max and I pretty much grew up in All About Town. I was selling Gold Lotto tickets way before I was legally able to do so, and my brothers, with their easy access to certain magazines, were very popular at school. My own weakness wasn’t so much capitalising on the magazines as the chocolates. I’d give them to boys I had a crush on. I still remember the day Mum said, ‘I don’t know, Brian, we just seem to always be running out of Mint Patties!’ Looking sideways at me, Dad had replied, ‘I can tell you exactly where those Mint Patties are going, Denise, they’re going to Paddy Parker, Paddy Wyatt and Paddy Sadler.’ My brothers had burst into laughter; I’d burst into tears and run for the refuge of the back office.

He’s always been very direct, my dad. In fact, there are times when his frankness borders on the ridiculous. Just last week, for example, I was sitting with Mum and Dad at Bits ’n’ Pizzas, Rocky’s local coffee shop, when Dad waved at someone coming in. ‘There’s old bloody Doug McRae—I thought he was dead!’

He’s also not backwards in coming forward with advice, even if you haven’t asked for it and don’t want it. Frustratingly, he’s often spot on. Mind you, he doesn’t always have a very nuanced take on things. Once, when Mum dragged him along to the ballet, he asked her when the dancers were going to start singing. When Mum explained that didn’t happen in ballet he said, ‘Well, I can tell you right now that’s not going to last.’

And just last week, when I told him how much the new mechanic from Brisbane charged to service my Corolla, he promptly declared, ‘Grubs don’t always live in the garden, love!’

If Dad’s black and white, then Mum’s fifty shades of grey, and I suppose that’s why they balance each other out. In her own way, Mum’s just as eccentric as Dad. I still remember the three of us kids, all squashed into the back of the Commodore, careering around these same streets, with Mum yelling at us to stop fighting. She’d then pull up out the front of St Joseph’s Cathedral and we’d troop in after her to Sunday mass, where she’d proceed to read from the lectern in what we liked to call her ‘church voice’. After mass we’d all hop back in the Commodore and recommence fighting.

Lenny and Max have both moved away from Rocky but at least Rosie, my crazy best friend from primary school, is still here. In fact, Rosie’s the only person keeping me sane at the moment—I always feel lighter in her company and my mood brightens as I remember she said she’d stop by this afternoon. Apparently one of her patients told her that Mum and Dad’s new next-door neighbours are moving in this week so she’s coming over to check them out. She and I have been trying to get to the bottom of who’s bought the place ever since it was sold, but not even my father, the unofficial mayor of Rockhampton, has any idea.

When Rosie and I aren’t playing Neighbourhood Watch, I’ve tried to establish a disciplined writing routine these past ten months. Essentially, I wake up, have breakfast, take Glenda for a run beside the Yeppen Lagoon, shower, then write for three hours, before discussing lunch with Mum. My regimen appears to be working because I’m almost halfway there with Diamonds in the Dust

, a sweeping multi-generational family saga set in the pioneering days of the Central Queensland gemfields.

Having set myself the goal of finishing my novel by the end of the year also helps me to justify my decision twelve months ago to leave my semi-glamorous life in Melbourne as a part-time, prime-time TV reporter and move to Port Douglas. At the time I’d rationalised it to my Melbourne friends and colleagues by talking about the weather and the hours I spent commuting.

‘It’s just too cold down here,’ I’d told my bewildered boss after she quizzed me about why I was leaving. ‘I’m from Queensland! I can’t hack these winters!’

In my heart, though, I knew the real reason I was leaving Melbourne was because I’d decided I was still in love with my ex-boyfriend, Jeremy, who’d got a job in Far North Queensland, and I wanted to rekindle our relationship. Unfortunately, by the time I’d moved north three months after we’d broken up, he’d decided he couldn’t see a future for us, and soon after he found the love of his life in Port Douglas.

And so, in a heartbroken daze, I stuck it out up there for about eight weeks picking up shifts reporting for WIN TV, before travelling south on the Bruce Highway and ending up back at Mum and Dad’s in Rocky, licking my wounds.

As I pull into my parents’ driveway, I’m relieved that the keen sense of my heart being wrung like a chamois every time I think of Jeremy has been replaced by a less intense emotional seesaw of feeling certain that I’m over him one minute, and completely lovelorn, having a Debbie Downer the next. I try to cultivate the former state by steering clear of Facebook, alcohol and anyone who might potentially mention him in passing. Within the comforting confines of Rocky, I feel like the heavy cloud of grief is gradually lifting, and the cloak of sadness to which I’ve clung is being gently pried away.

As I get out of the car, Glenda runs up to me, tail wagging enthusiastically. ‘Hi, little mate!’ I say, giving her a hug. Distracted, she breaks away from me and bolts towards the fence, looking around to see if I’m following her. I realise that the source of her excitement is not my arrival but two men who are standing in the driveway next door. In fact, it’s all I can do to stop her leaping over the fence to go and give them a lick.

After coaxing a reluctant Glenda inside with promises of liver treats, I shut the front door and call out, ‘Hey, Mum, it looks like we’ve finally got new neighbours.’

There’s no reply from Mum, who I find in the lounge room, drumsticks in hand, intently watching an African man’s bongo drumming performance on DVD. Since selling All About Town, Mum has gone from one craze to another, and African drumming appears to be the latest. If it’s not crystals, it’s calligraphy or colouring in. And don’t get me started on Cher—Mum’s absolutely obsessed with her.

‘Ma! You’re in your African drumming trance again!’ I say.

‘No, I’m listening, love,’ she replies distractedly, not taking her eyes off the screen.

‘Well, what did I say?’ I sink down into the couch.

‘You said they’ve moved in next door.’

I nod and pick up a MiNDFOOD magazine, but its barrage of articles on how to attract money through mantras leaves me feeling flat, and I sigh heavily.

Mum pauses the DVD and turns to me. ‘Are you a bit down, love?’

‘No, no,’ I say, giving her the brightest smile I can muster.

‘Lucy, what’s wrong? Have you heard from Jeremy?’

‘No,’ I reply. ‘I don’t think I’ll ever be in contact with him again.’

‘Tell me what it is then,’ Mum persists. ‘I know something’s troubling you.’

‘I’m fine, Ma,’ I reply. ‘Cup of tea?’

‘I’d love a cup. Make me one of those Rooibos ones, would you, darl?’

I nod, head to the kitchen and put the kettle on. After I get the milk out of the fridge I pause and stare at the photos of my happy siblings smiling at me from beneath an assortment of magnets. There are pictures of Lenny and Camille’s beautiful wedding in Sydney beside similarly joyous snaps of Max and Brooke at the launch of Fancy Pants, their new online business selling bamboo nappies into China. Then there’s the pics of all five of my nieces and nephews in various poses. Suddenly the milk I’m holding feels as heavy as my heart.

‘Are you making tea, Lucy?’ says Dad, interrupting my reverie as he strides into the kitchen.

‘Yep. Want one?’ I ask, turning around.

‘Yeah, thanks,’ he says, then hurries off. Dad seems busier in retirement than he’s ever been. He’s always doing stuff at the Jockey Club, which is weird because I don’t remember him ever being that into horseracing. Then again, he worked pretty much six till six in the newsagency before he retired so he didn’t have much time for anything else.

‘What are you thinking about?’ Mum has come to stand beside me as I gaze absently at the whistling kettle.

‘Whether I’ve eaten all those Crabtree & Evelyn choc-chip biscuits.’

Mum laughs but still looks worried.

‘Oh, I don’t know, Ma,’ I say. ‘I did my tax with Todd Doherty and it’s not pretty. Sometimes I feel like it was a mistake leaving Melbourne, and it’s all too late now.’

‘Too late for what?’ asks Mum.

‘Too late to have a career, and to have excelled at just one thing.’

‘Lucy, you left Melbourne because producing wasn’t what you wanted to be doing, and it was a juggle to combine it with any presenting,’ says Mum. ‘You were working long hours, and travelling back and forth all that way to even get to work. Plus the rent was ridiculous and the weather was miserable. You left because you weren’t happy down there.’

I nod, aware that what Mum’s saying is completely true.

‘It’s easy to only remember the good things in hindsight,’ Mum continues. ‘It’s the same with Jeremy. Yes, you had fun times together, but you also had your doubts about the relationship, which I think you’re forgetting.’

I nod again, knowing she’s right.

‘You have to stop fooling yourself that things were perfect in Melbourne.’

‘Mmm, I just think—’

‘You can think too much,’ says Mum, cutting me off. ‘Just the other day I read an article by Deepak Chopra, and it was so true what he was saying.’

‘What was he saying?’

‘How it’s a waste to live inside your head, and that we should be more like nature, just existing and breathing, and being open to the universe.’

‘Ha! I went to see Deepak Chopra speak when he was in Melbourne,’ I say as I jiggle the teabags, ‘and he went on and on about how if you followed his advice you could have the perfect body, the perfect mind and perfect health. And he had the most shocking sinus I’d ever heard.’

Mum laughs. ‘He didn’t!’

‘Yeah, he’d be saying how we can command our bodies to overcome anything, and then he’d clear his nose like he had the worst dairy allergy known to man.’

‘Oh, Lucy, really?’

‘Yes, really. So I’m not sure you should give too much credence to Deepak,’ I say, chuckling, as we return to the lounge room with our teas.

‘So, they’ve finally moved in, have they?’ says Mum, looking out the window just as the sound of a bike clunking onto our front verandah is followed by the door slamming.

‘Who’s moved in?’ asks Rosie, resplendent in lycra, as she sweeps into the room, unbuckling her bike helmet.

‘You, with the amount of time you spend here!’ jokes Mum.

I think Rosie would probably be popping in for an afternoon cuppa regardless of whether I was around. Last week she was in the kitchen chatting with Mum for an hour before I emerged from a morning session of writing in my bedroom to find them huddled over the latest HomeHints Direct catalogue, discussing the benefits of extra-long oven mitts. The two of them have delighted each other ever since Rosie first turned up at our house with a sleeping bag, aged six, and said to Mum, ‘Turn up this song, Mrs Crighton, I love it!’ The song happened to b

e Mum’s favourite—Cher’s ‘If I Could Turn Back Time’. Rosie also speaks back to Dad with the cheeky familiarity that comes from being one step removed.

For me, Rosie has always been a portal to a different world, a world without rules. I can vividly remember us as children at her parents’ house one Saturday night, drinking coffee milkshakes at midnight while we watched Flowers in the Attic. We were only in grade three at the time. My parents would have been horrified if they’d known.

Her loud, sunny nature is the perfect antidote to my introspection. When I get lost in my thoughts, she’s always there, with a torch, guiding me out of the wilderness of my mind. Unlike me, she doesn’t care what people say or think about her. If someone’s an arsehole, she’ll tell them to fuck off, then forget about it, whereas I’ll create a flowchart to understand the sequence of events that led to my mistreatment.

Mum and Rosie are reading their horoscopes to each other and laughing when Dad bustles in with two different ties draped around his neck. ‘Denise! Denise! I need you to focus,’ he says, clapping his hands and gesturing at two ties.

‘Oh, Brian, for heaven’s sake, I’m just here,’ says Mum.

‘Blue or red?’

‘Red,’ says Mum.

‘Rosie?’ asks Dad.

‘Red.’

‘Lucy?’

‘Hold the blue up, Dad,’ I say, and then pretend to give both options weighty consideration. ‘Red.’

‘Right. Well, I’m off to the Jockey Club,’ he says, putting the red tie on as he marches towards the front door.

‘You’ve got a cup of tea you asked for there, Dad,’ I say.

‘Too busy!’

‘Hey, Brian, leave us your wallet!’ Rosie calls after him.

‘Get a full-time bloody job, that’s the answer for you!’ Dad calls back, laughing, as the door bangs shut.

‘Yeah, right, as if spending forty hours a week looking into people’s mouths and dealing with kids who eat too many bloody lollies freaking out while I do their fillings would improve my life,’ says Rosie, chucking a WHO Magazine onto the coffee table and picking up a copy of HELLO!. ‘Fat chance. So, are there any husbands next door for you or what?’

Girl in Between

Girl in Between