- Home

- Anna Daniels

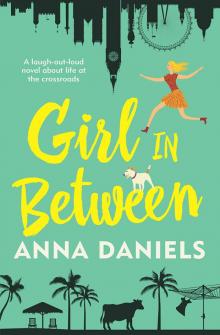

Girl in Between Page 12

Girl in Between Read online

Page 12

‘Actually, I’m going to get the lovely woman’s number—and a ciggie,’ she says, blowing me a kiss and skipping off.

‘I love Rosie,’ I say to Ben, who’s watching her duck and weave across the beer garden.

He turns around and we hold each other’s gaze. ‘You have such beautiful hair, Lucy,’ he remarks, reaching across the table and twirling his fingers through my curls.

‘Thank you,’ I reply, smiling. ‘Thank you, Ben.’ I pause. ‘Want to go get a Subway?’

The next morning, I wake with a pounding headache, an urgent thirst and a hand around my waist.

I frown as I realise I’m in one of Helen’s bedrooms and then gasp as I look over my left shoulder and see Ben. He opens his eyes lazily as I sit up.

‘You were spectacular!’ he says.

I swallow hard and lie back down. The last thing I can remember is sharing a six-inch meat-and-cheese with Ben, then slow-dancing with him as he sang ‘Wonderwall’ in the cab queue. I groan as memories begin crowding into my throbbing head. There’s a flash of me unbuckling Ben’s seatbelt and him putting his hand up my top, and of me pinning him against the fridge after we devoured leftover lasagne. I remember texting Mum that I was staying with Rosie, then … nothing.

Ben reads the mortification in my eyes.

‘Relax, Lucy, I’m just joking,’ he says, withdrawing his hand from my waist. ‘We got off to a good start and I’d hoped to try some of my charming moves but you passed out. Nothing happened.’

‘Thank God!’ I say, a little too emphatically, just as my foot brushes against my jeans, which are curled up at the base of the bed. I reach between the sheets and pull them on. ‘Sorry, Ben,’ I add, feeling nauseous with the sudden movement. ‘I don’t normally ever just black out like that. Bloody hell.’

‘It’s okay,’ he says. ‘We had fun.’

‘Ben, I—’

‘I know,’ he says. ‘I want Oscar to know about this just as much as you do.’

I now feel violently ill. Ruth must have told him.

‘Oscar?’ I ask quietly, attempting to look puzzled.

‘He’d skin me alive,’ he continues. ‘It’s been obvious since that first barbecue he’s half love-sick over you. Whenever he’s at Mum’s he’s always wandering over to the window to look down at your house.’

‘But he’s got a girlfriend,’ I say.

‘Yes, but he’s definitely into you,’ he replies, staring at the ceiling. ‘Look, don’t worry. There’s nothing worth saying about this. Nothing happened.’

I remain silent, thinking.

‘You’re a great chick, Lucy,’ says Ben eventually. ‘Of course I love old Oscar, but don’t take any crap from him.’

‘What are you—?’

‘I’m not really trying to say anything. Except that Oscar’s a guy who can have any girl. Through no fault of his own he’s used to getting what he wants, even if he doesn’t know it.’

Maybe Ruth didn’t tell Ben after all. This is the only thought I wish to consider right now, not the deeper and potentially more distressing observation about Oscar that Ben’s just made.

I look over the side of the bed and see my top.

‘Your mum?’ I ask with alarm, pulling my top on and standing up.

‘In Sydney with Oscar,’ he replies. ‘Good thing too. The kitchen’s in a bad way after we tried to make banana bread.’

‘Banana bread?’ I shake my head in disbelief.

‘Yeah, you insisted. Said your banana bread won ribbons at the local show or something. You wouldn’t come out of the kitchen!’

‘Oh God!’ I say, rubbing my forehead.

‘So we put on one of Mum’s Phil Collins CDs, and when “A Groovy Kind of Love” came on you burst into tears and ran to the bedroom.’

I look at him, feeling equal parts aghast, embarrassed and thoroughly entertained.

‘I found you asleep in your underwear,’ he adds.

‘That song always gets me,’ I reply, as if it’s the perfect justification for my behaviour. ‘Sorry, Ben,’ I add, walking to the door. ‘Sorry I put you through all that.’

‘You didn’t put me through anything,’ he replies. ‘Don’t be sorry.’

I turn the door handle. ‘So we’re not going to ever mention this again?’ I confirm.

He nods. ‘Lucy,’ he says as I open the door, ‘do you like him? Oscar?’

‘Yes,’ I reply. ‘I like him.’

I skulk in to Mum and Dad’s and it sounds like World War III has broken out in the kitchen, with ‘Kakadu … selfish …’ ringing out in Mum’s voice, followed by ‘bloody chakras … stupid bongo drums …’ in Dad’s. I sneak into the lounge room, grab my car keys, then tiptoe back out the front door and drive to Rosie’s.

‘Ben?’ she asks, opening her front door.

‘Yes and no,’ I reply. ‘Pat?’ I ask, noticing the red marks on her neck.

‘No,’ she says, letting me in.

‘Todd Doherty?’ I ask, puzzled. ‘Did you link back up with him?’

‘No,’ she answers as we walk into her kitchen.

‘Who then?’ I demand, before my mouth falls open and Rosie starts to laugh quietly.

‘Dave!’ I exclaim.

‘Shhh!’ she says. ‘He’s still in there.’

‘My cousin Dave?’ I whisper. ‘Hilarious!’

‘I tell you what, Luce, under that flanno is a wild cowboy! The moves he was pulling on—’

‘Stop it, Rosie, you’ll make me sick,’ I say, putting my hand over her mouth.

I sigh heavily and lean back against the sink as she pours a glass of water and hands it to me.

I gulp it down and then say, ‘Rosie, do not be leaving me in this state today. If you do, I’ll be calling Oscar. I’ll be calling Jeremy. I’ll be contemplating throwing myself off the top of Mount Archer. The works.’

‘You’re over Jeremy,’ she says.

‘I wouldn’t put anything past me today,’ I reply.

She rubs my back. ‘I’m fucking famished, Luce.’

‘Me too. What’s open this early?’ I ask.

‘Red Rooster. We could dine in.’

‘Oh, mate,’ I reply. ‘We are sinking to new lows in this town.’

‘I know,’ she says. ‘What am I going to do about …?’ She nods in the direction of her bedroom.

‘Leave,’ I say.

‘Oh, I can’t just leave! That’s rude and awful.’

‘Well, write a note then.’

She rips a piece of paper titled Shopping List from behind a magnet on the fridge, and hovers above it with a pen.

‘Can you write it?’ she asks, looking over at me.

‘Me?’

‘Well, he’s your family! Just pretend you’re me.’

‘Oh, righto,’ I say and scribble across the page.

‘Luce! I can’t just write “Good on ya, Dave!”’

‘Do you want to pursue something with my cuz?’ I ask, eyeballing her.

She shakes her head quickly and we leave the note under an orange on the kitchen table.

Sitting in a booth at Red Rooster, Rosie and I murder a family pack of chicken rolls, nuggets and chips.

‘Right, so you’re eating now, which means you can talk. I cannot believe you woke up with Ben!’ she laughs.

‘Neither can I!’ I exclaim. ‘Those bloody pills! What the hell did we take?!’

‘You’ve also got to remember that we each had about eight UDLs.’

‘I definitely kissed him,’ I say. ‘I think he had his hand up my top at one stage. And I remember body slamming him against the fridge door and nibbling on his ear.’

She lowers the chips from her mouth and starts shaking with laughter. ‘Lucy Crighton, you are out of control! You do know that Ben’s related to Oscar?’

‘I didn’t mean it! It was those pills!’ I put my head in my hands. ‘What have I done?’

‘He says you didn’t shag him, so that’s okay,’ Rosie sa

ys quickly to counteract my distress.

‘No, thank goodness,’ I reply.

‘Ben’s not going to say anything,’ she continues. ‘And he’s leaving in a few days to walk the Camino.’

‘What?’ I ask, startled.

‘Yeah, he told me last night. He’s pretty lost. Poor bugger. I think he’s hoping some sort of answer to all his questions will be whispered to him as he’s trekking through the Pyrenees.’

‘Maybe it will be,’ I say, feeling sad for Ben, but also relieved I won’t risk running into him.

‘There never is,’ says Rosie. ‘Only what you make up in your mind.’

I mentally sift through the events of the last twenty-four hours, assessing whether the news of Ben’s imminent departure paints what happened between us in a new light.

‘Lucy, get over yourself and stop worrying,’ says Rosie sternly. ‘You were trying to bake banana bread at three in the morning, I was in the bath with your cousin Dave, and Ben was trying to get you in the sack. It was the pills talking, nothing else.’

I nod and push the chicken roll away, feeling suddenly ill at the image of Rosie and Dave in a bath.

In better spirits after our Calippos, I drive us to the cinemas over on the north side and watch the only film screening that afternoon: Hotel Transylvania 2. Such is my fragile state that I cry when Dennis leaves the hotel and flees to the forest, while Rosie sleeps through most of it.

‘Luce,’ she says as we emerge from the darkness of the cinema into the dusk of the car park, ‘I’m gonna move to London.’

The next morning, I awake at an ungodly hour to the sound of Roomba outside my bedroom and Mum bustling about on the back deck, singing Foreigner’s ‘I Want to Know What Love Is’. My feelings of outrage over Roomba are somewhat offset by my relief that she’s sounding brighter.

Last night, after I got home from the cinema, I’d found her in tears again. And for some strange reason she’d emptied the cutlery drawer onto the kitchen table and was sifting through the spoons. I did what I always do when I don’t know how to cope with Mum. I called Max and put her on the phone to him. Within minutes she was chuckling down the line.

‘While you’re off gallivanting around Kakadu, I’m going to China with Max to tour the Fancy Pants factory outlet, and I’m going to tack on a Qi-Gong trip through Mongolia with Master Ray and his students,’ she’d said to Dad without drawing a breath, then firmly shut the TV room door, wiped away her tears and replaced the cutlery drawer without a second glance as to whether the knives matched the forks.

‘Mum!’ I yell out now as she continues singing. ‘What are you doing?’

‘I’m recharging my crystals, Lucy,’ she replies, as if it’s perfectly obvious what she’s up to at 5.30 am on a Wednesday. ‘I need to take advantage of this morning light.’

‘It’s too early, Ma!’

‘Rubbish!’ she calls back through the flyscreen. ‘Glenda and I have already been out for a walk, had a cup of tea and hung out the washing.’

‘Jeez, that dog’s multi-talented,’ I say. ‘We’ll have to post a video of her hanging out the washing on YouTube.’

I close my eyes, hoping to rejoin those happy souls in the Land of Nod, then jump in shock at the sound of Mum whispering, ‘Come and sit outside with your poor old ma.’

‘Hooly-dooley, Ma!’ I exclaim as she starts laughing, her forehead and nose pressed against the flyscreen of my window like Freddy Krueger. ‘You frightened the wits out of me!’

I join her outside on the swinging chair, the day still breaking before us on the back verandah. Despite the winter winds, the hardy bougainvillea continue to bloom, adding flashes of brilliant maroon and pink to the burnt orange hues of sunrise.

‘There’s something nice about watching the clothes dance in the wind, don’t you think?’ asks Mum.

‘Yeah, there is,’ I reply. ‘I think it’s because you’re achieving something, there’s an outcome at the end of it.’ I snuggle up to her. ‘It’s getting cold.’

‘It is,’ she agrees. ‘There’s flannelette sheets in the cupboard, you know.’

‘Mmm,’ I reply.

‘How was your night at the Whipcrack with Rosie?’ she asks. ‘I feel like I’ve hardly seen you since then.’

‘Yeah, good,’ I say. ‘Rosie’s pretty set on London.’

‘Is she?’

‘Yeah. She’s a bit over Rocky.’

We swing in silence, both grim at the prospect of losing Rosie to England. Still thinking of her, I say, ‘Dave Conroy was at the Whipcrack.’

‘Ah, lovely Dave!’ She smiles. ‘Have they had much rain out that way?’

‘A few inches,’ I reply.

‘Remember when he used to chase you around and try to pull your pants down?’ she says. ‘I think I’ve still got a photo of you two having a bath together as whippersnappers.’

I wrinkle my nose in disgust, then smirk as I think how it’s not my pants he’s trying to pull down these days, and that Rosie isn’t the only one who’s bathed with Dave.

‘I went and saw Meredith yesterday,’ says Mum. ‘She’s not good at all.’

‘Isn’t she?’ I ask.

Meredith is a sweet, gentle soul who used to spend a few hours each week repositioning clothes on mannequins at All About Town. I think even she knew her work wasn’t essential, but she loved being with Mum and always said I looked fabulous when I played dress-ups with the stock as a little girl. Earlier this year she had a stroke, and now she’s living in the high-care ward of a nursing home with people almost double her age.

‘No,’ says Mum. ‘It makes me sad to see her like that, just lifeless and empty when she used to be so sprightly and independent.’

‘Does she still recognise you?’

‘She always smiles and tells me how busy she is, but I don’t think she really knows me. I hold her hand but I’m not sure if it makes any difference.’

Mum looks beyond the trees in the backyard to the mountain range, now aglow with the rising sun. Lately, I’ve noticed a subtle shift in her. She’s starting to take naps in the afternoon and is getting weary again by the early evening, and as we swing back and forth I get a keen sense that this person, whose presence I love but have taken for granted for so long, won’t always be around.

I can remember having the same sensation of impending loss with my grandma. One day when I was about fifteen years old I was studying at our dining room table and looked up from my books to see her in the kitchen, emptying plates and cups from the dishwasher into her wheelie walker basket and shuffling along with them to the cupboard. I took the whole scene in and freeze-framed the moment, hoping to preserve it in my mind. These moments, which range from the heartbreaking to the hilarious, help me to map my journey. The beauty and the sadness, I think, lies in the moment of recognition, when you realise what you’re seeing is so stirring, yet so fleeting.

This morning, I freeze-frame Mum, hoping I’ll always recall this image of her, sitting beside me, staring distantly at the breaking day and the dancing clothes.

I spend the rest of the morning working on my novel, and am pleased with how it goes. My heart sinks, however, when I go to the ATM to get twenty bucks out for a coffee and am greeted with a screen telling me I have ‘insufficient funds’. It’s well and truly time for me to get a few more freelance jobs.

That afternoon, I walk along Quay Street with the one- and-only business card I have left. When I rang Rosie to tell her about my ATM fiasco she said one of her patients had mentioned a production company that has just started up in Rocky. Though I suspect all they’ll be doing is producing low-budget TV commercials for places like Bits ’n’ Pizzas and Gone Bush, I haven’t made any money since my vet articles—and I figure producing ads is better than washing cars with Ruth. I’ve also realised that devising any sort of plan requires cash.

A sign with orange lettering against a gleaming white background announces my arrival at Matchstick Productions. I square my shoulde

rs, take a deep breath and tell myself to be confident. I have years of experience working as both a radio and TV producer. They would be lucky to have me. I slide the business card from my wallet and walk inside.

‘Hello,’ says a friendly woman behind the reception desk. ‘Can I help you?’

I take heart in her conviviality and hand over my card, saying, ‘Hello … Ah, my name’s Lucy Crighton. I’ve worked for TROPPO FM, Sky News in Perth, WIN TV in Port Douglas, The Headline Act …’

The woman nods encouragingly as I list my former employers.

‘And I’d love to work for Matchstick Productions,’ I conclude enthusiastically.

‘Ah, look, that all sounds great,’ she says, thumbing my business card, ‘but we actually produce … matchsticks.’

‘Oh,’ I reply, overcome with humiliation and hilarity simultaneously. ‘Sorry.’

As I leave Matchstick Productions I burst into laughter. The only downside, I think, as I lean against my car cracking myself up, is that I just gave my last business card to a timber mill!

Arriving home I walk along the side of the house, following the sounds of Mum and Rosie on the swinging chair, flipping through the latest HomeHints catalogue.

‘The thing is, Denise,’ Rosie is saying, ‘as you get older your knees go, so this Weed Remover with Ejector would actually be quite handy because it allows you to remove weeds while standing, see? Look at this picture. No more bending.’

‘Hmmm,’ replies Mum. ‘Could be a very useful tool. Your mum might also like one, Rosie. I wonder if they’d give us a discount if we bought three.’

I roll my eyes and stay there a bit longer, listening to them discuss Mum’s upcoming trip to China and Mongolia and Rosie enthusing about going to London.

When they start talking in lowered voices, it can only mean one thing and as I lean against the brick wall I hear Mum say, ‘Rosie, you know Lucy can’t go to London.’ The creak of the swinging chair fills the silence between them. ‘She needs to finish this damn novel and figure out what she wants to do next. And I just don’t think London’s the answer.’

‘Well …’ Rosie begins then stops. ‘She’s on track with her writing. She’s been working really hard.’

Girl in Between

Girl in Between